Reframing Responsibility

Many of us will by now be familiar with the idea of a carbon footprint – a measurable mark of our environmental impact. But fewer might know its curious and somewhat cynical origin. The term was popularised not by ecologists or activists, but by advertising giant Ogilvy and Mather, on behalf of BP, in 2003. The oil company, facing growing scrutiny for its role in climate breakdown, shifted the spotlight. “It’s not our fault,” the campaign whispered, “It’s yours.”

And so, a story was spun: a story of personal culpability conveniently eclipsing structural responsibility. And I’ve started to wonder if schools have been spinning a similar tale.

Looking Outward, Looking Away

For as long as we’ve named and noticed the rise in mental ill health among our children and young people, we’ve looked outward for the cause. We’ve seen this reflex in the moral panic around The Anxious Generation, in Netflix’s glossy dissections of digital adolescence, and in the quiet creep of certain strands of character education or social-emotional learning. We name screens and social media, Andrew Tate and toxic masculinity, “helicopter” parents or “snowflake” students – often in tones that suggest a failing, a flaw, a fault, in the child and their family.

And of course, these forces matter. They muddy the waters our young people must wade through each day. It would be naïve to pretend otherwise. But the tendrils and roots of the mental health crisis amongst children and young people are supported and fed by multiple causal factors. As always, complex problems are made worse by a reductive attempt to apply simple solutions.

The Unseen Complicity of Systems

I cannot help but feel a growing unease – a recognition that, just as BP sought to shed its responsibility by reframing a systemic issue as a personal one, we in schools may have done something similar. We’ve become experts at seeking the signs and symptoms of external harm, painstaking in our safeguarding, tireless in our pastoral vigilance, but far less willing to look at the ways the system itself may be complicit.

And I say this not from a pedestal, but from within the architecture. I’ve been an educator for nearly thirty years, a leader for most of those. My own fingerprints are on the policies, the protocols, the practices. I have tried – sometimes desperately – to protect children from harm, whilst upholding a paradigm that, unwittingly, has helped to cause it.

“…wellbeing is not an outcome, but a guiding principle,”

Because here lies what I am tempted to call the ‘safeguarding paradox’. We would never deliberately harm the young people in our care, and we are better than ever before – thanks, for example, to the tireless effort and proliferating expertise of such critical initiatives as the International Task Force on Child Protection – at preventing harm. Yet we have inherited, and too often sustained, a system that does precisely that. And this is where I want to propose a new lens. One I’m calling the wellbeing footprint.

Introducing the Wellbeing Footprint

Each day, in every school, educators and leaders make hundreds of decisions: about curriculum and pedagogy, assessment and behaviour, leadership and communication. The list is endless. But how often do we pause to consider the wellbeing footprint of those decisions?

Whilst we prioritise performance, do we intentionally nourish self-worth? We punish and we reward, but do we reflect on the shame we might sow, or the dependence we might develop? We celebrate the students at the summit, but do we embrace (or even see) those in its shadow?

We speak the language of diversity, equity and inclusion, yet our leadership remains steeped in sameness and power preserved in familiar hands. We design learning for compliance and quiet, while our classrooms brim with divergence and difference. We speak of impact, but too often the numbers we track often drown out the truths we cannot.

A Quiet Reckoning

The wellbeing footprint, then, is not an accusation. It is a question. A quiet, persistent one.

What residue does each decision leave in the hearts and minds of those it touches? Whose thriving is served, and whose is sacrificed? What does it cost, not in what’s easy to measure, but in what’s hardest to restore: belonging, dignity, hope?

“To ask these questions… is to choose curiosity over certainty, accountability over defensiveness, and compassion over compliance.”

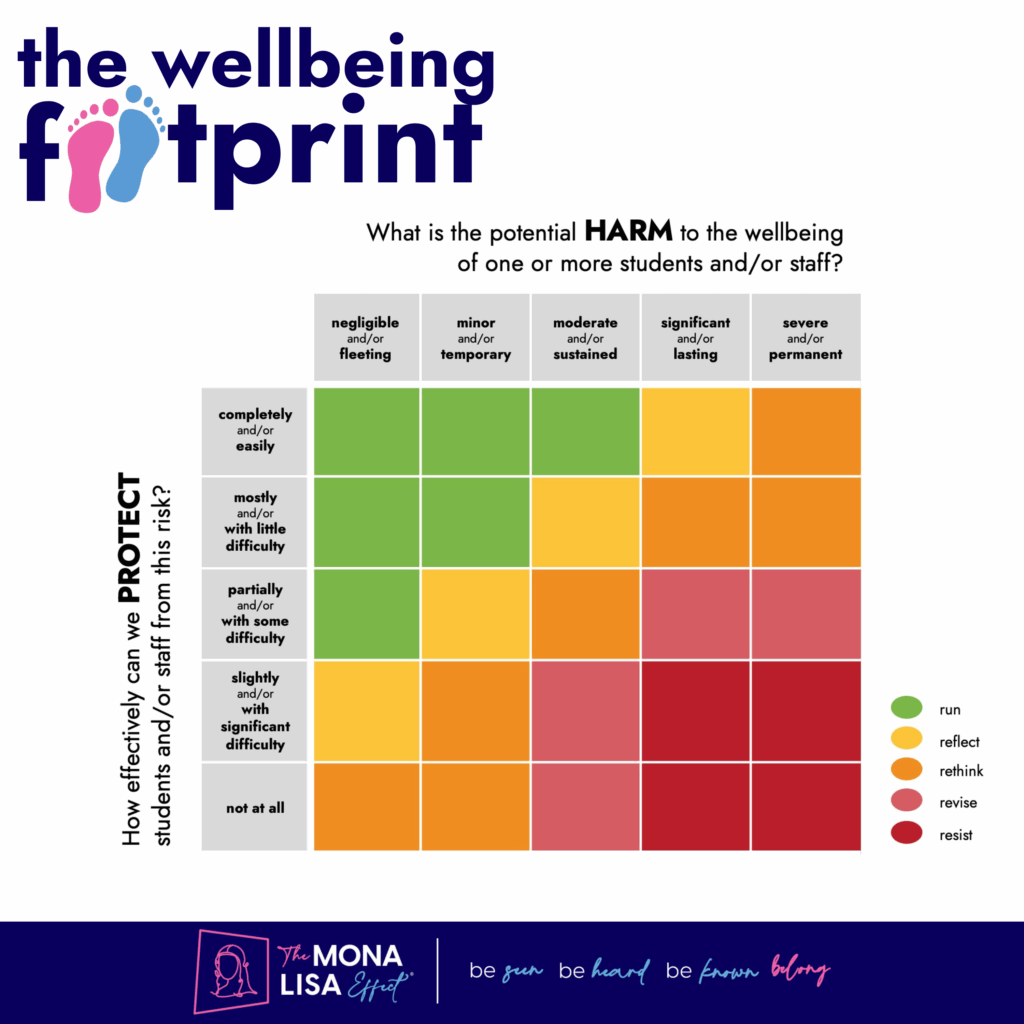

In this work, we are mapping these traces. Not in metrics, but in moments. The ‘wellbeing footprint’ matrix invites us to chart not only what we do, but what it does – to whom, how, and why it matters.

We wanted to raise standards. But what else did we raise? Anxiety? Attrition? A quiet sense of never-enough?

We track attendance, behaviour, progress. But what don’t we track? Who’s holding their breath? Who’s shrinking to fit?

We redesigned the timetable. But did we ask who it was designed for? Or who it left behind?

Are we preserving what works for us, or noticing what doesn’t work for them?

Figure 1. The ‘wellbeing footprint’ matrix (version 1.0) © Matthew Savage 2025

Try it. Take a practice. Any practice. A rule enforced, an instruction given, a seat assigned, and ask what it leaves behind. Plot a single policy. Follow its ripple through routines, through relationships, through rows of desks. Choose a thread – a rota reworked, a policy written, a timetable drawn – and follow where it frays.

A Gentle Invitation

To ask these questions is not to demonise us as educators and leaders, or to malign the schools in which we educate and lead. It is to dignify our profession with the honesty it deserves. It is to choose curiosity over certainty, accountability over defensiveness, and compassion over compliance.

Of course, our epistemological toolbox must be nuanced, adaptive, and varied. Because, after all, to ask, “What is, or might be, the wellbeing footprint of this decision?” is also to ask, “How do I know?” And, in any case, it is the process that is so much more valuable than the product. The intent is not somehow to produce a neatly scored grid for every decision made or contemplated – how arduous and impractical that would be! Rather, this is about mindset and shifting our own.

We can’t compost our way out of this crisis with mindfulness apps and SEL add-ons. We need to tend the soil and nourish the roots. And so, I offer this not as indictment, but as invitation: to step gently into a new kind of reckoning. One in which wellbeing is not an outcome, but a guiding principle. Not a supplement, but a structure. Not a poster on the wall, but the earth from which everything else grows.

Because just as every product leaves a carbon trace, every decision leaves a wellbeing one. What if the measure of a good school were the gentleness of its footprint?

By Matthew Savage

Architect of The Mona Lisa Effect®, Matthew Savage is an internationally respected educational consultant, speaker and former school Principal, whose work explores the nexus of wellbeing and DEIB in schools, through a range of radical new ways of knowing. Matthew draws on the intersectional soup of his own family, together with almost 30 years working in and with education and school leadership, to challenge the ways in which schools define, deliver, and enshrine inclusion. A board member for two international schools, and a member of the Advisory Board for Parents Alliance for Inclusion, he now works with schools around the world to help them transform their spaces, systems and cultures into environments where everyone – without condition, exception or compromise – is seen, heard, known, and belongs.